In the last post, I mentioned that I had formulated a method

where one could use a quantitative easing and the balance sheet of the central

bank to carry out a debt jubilee. The original text was posted on my Icelandic

blog:

Framkvæmd skuldaniðurfellingar. The original idea of this comes from

Steve Keen but, I believe, the

actual process is slightly different with the addition of the Special Purpose

Vehicle.

The main difference is that there is no net increment of

money supply while the effects on cash flows are more or less the same. One of

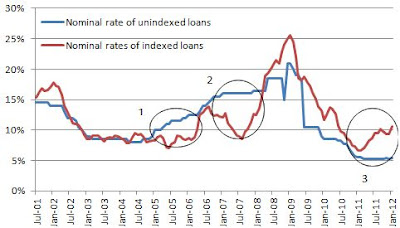

the many serious problems in the Icelandic economy is that the principals of

majority of mortgages are indexed to the Consumer Price Index. Therefore, a

version of Keen’s modern debt jubilee – which he discussed e.g. in

HardTalk and in his book,

Debunking Economics (in the chapter “Monetary Model of Capitalism”) – had to be

formulated where there was no, or very limited, risk of a spike in inflation,

which would inevitably end up with the jubilee being useless as principals of

mortgages would grow once more.

The act itself

First, a Special Purpose Vehicle is founded. It can have

equity of one pound, that doesn’t matter. The SPV will borrow a particular

amount from the central bank and in the Icelandic blog post I mentioned 200

billion ISK (1 billion GBP) or about 13% of book value of debts of Icelandic households (the face value is much higher, probably close to 2,000 billion ISK vs. 1,500 billion of book value). The central bank pays out the loan into the

deposit account of the SPV at the central bank itself.

The SPV then pays out the whole amount into the deposit

accounts of individuals. The amount that each gets is a certain proportion of

the each individual’s outstanding debt (this can be done differently of course,

all indebted borrowers may e.g. get a fixed amount of money instead of

proportion of their debt). But as soon as the money has been paid out to

individuals, the same money is used to pay down the principal of their debts and not used for anything else.

By then, the money is at the banks. The banks then deposit the whole amount at

the central bank.

By now the money has gone the whole circle: the central bank

lent money to the SPV, which paid it out to individuals, who used it only to

pay down their debts at banks, which then channelled the whole lot back to the

central bank.

After the act

The balance sheets of all the players are now the following:

The central bank has expanded its assets by the amount of

the loan to the SPV. Its liabilities have expanded as well in the form of

higher bank deposits at the central bank. The equity is unchanged but the

leverage has increased.

The banks have lost the amount repaid on loans but gained

deposits at the central bank. Debts, amongst them households’ deposits, are

unchanged. Leverage is unchanged.

Households have decreased their debts by the amount repaid.

Their assets are unchanged. Equity has increased by the amount repaid. Leverage

has decreased.

The SPV owes the whole amount to the central bank but

doesn’t own anything. Its equity is therefore negative by the amount it

borrowed from the central bank and paid out to the households.

But the SPV is not

bankrupt

Here, one has to remember what “bankruptcy” is. To be

bankrupt is to be unable to repay your debt at the time they are to be repaid!

This is not the same as to have negative equity, i.e. debts

higher than assets. If an individual is able to find income, such as from work,

to repay his debts every month, he is not bankrupt. About 60,000 households in

Iceland (40% of households) are in the state of negative equity (I believe the

street-wise term would be “technically bankrupt”) but many of them are, still,

able to find wage income to repay their high financial debts every month. So in

the meanwhile, they are not bankrupt.

An individual or a corporation can also just as well go

bankrupt even though their assets are higher than their debts. A classic

example is a commercial bank, where the value of assets is higher than that of

debts, that experiences a bank run: if the bank does not have enough liquidity to

satisfy the depositors as they demand repayment of their deposit, the bank goes

bankrupt because it cannot pay its debts back when they are to be repaid. Naturally,

a central bank normally steps in to repel the bank run by lending liquidity to

the bank which is repaid later when the bank run has receded.

The same applies here regarding the SPV and the loan from

the central bank. Its stipulations are the following: the bond – it can have no

interest rates but there are (in Iceland) some arguments for it to be indexed

to the Consumer Price Index – is only repaid when the banks profit. And it is the

banks that repay it, i.e. they pay the SPV a certain part of their annual profits which the SPV uses to pay back the loan. This has two consequences: the SPV will never go bankrupt

unless the whole banking system collapses and there are limits to how high the

loan can be due to lower net interest income of the banking system.

This repayment of the loan by the banks on behalf of the SPV

can take many years or decades. It hinges on many things such as the profits of

the banks, the share of profits that are used to repay the loan, the dispersion

of profits of the banks, etc. In the case of Iceland, the amount that has been mentioned is 200 billion ISK (1 billion GBP or 13% of Iceland’s GDP). In comparison, the

banks have amassed profits amounting to 167 billion ISK since their collapse in 2008.

We are not fighting a banking crisis in Iceland; we are

fighting a household debt crisis which will, if not stopped, drag the whole economy down into the abyss.

But what of the

connection between the SPV and the banks?

Now, many people will stop and ask: what about the

connection between the banks and the SPV? Why does the SPV’s debt not impact

the banks equity?

Because it’s an off-balance sheet financing, a very common

trick in the world of finance whenever you want to hide debts. The banks are

vouching for the repayment of the debt but it isn’t their debt. That repayment

is only carried out as a share of their annual profits and only when they

profit. And only when they profit!

In fact, this trick is used in Iceland already. The Housing

Financing Fund is an official non-bank entity that raises funds on the capital

markets, mainly from the Icelandic pension funds, and lends out the money to

anyone who wants to buy a house. The State vouches for the HFF’s ability to

repay its debts – but that does not make HFF's debt the State’s debt. This

guarantee was estimated to be equal to 928 billion ISK (nearly 5 billion GBP)

at year end 2010 (total State Guarantees are 1,305 billion ISK, just short of

85% of GDP) but this guarantee does not show up on the State’s balance sheet,

even though the guarantee is there and the State had to pump equity of 33

billion ISK into the HFF in 2010 due to (State suggested and sponsored) loan losses.

The format of the SPV would be the same. The SPV would be

vouched for by the banks but like the State guarantees, that would not show up

on the banks balance sheets. Just to be clear though, in the case of Iceland,

accounting rules would have to be changed according to info from an Icelandic

accountant. How much, I do not have a clue.

The cost of the

jubilee is shouldered by the banks

So the cost of the debt jubilee is not carried by the

Central Bank, in the form of lower equity, nor by the State, but the owners of

the households’ debt, i.e. the banks. And to emphasise it again: the equity of

the players involved, beside households of course, does not change by the act

itself.

The cost is carried in the form of lower interest income of

banks. Exactly because of this, the amount repaid (the amount of the loan from

the central bank) cannot be too high. When the funds have made their loop from

and to the central bank again, the net-interest-income-creating stock of banks’

assets and liabilities has been transformed: their debts in the form of

households deposits are the same but part of the banks’ high-yielding

households loans has been transformed into low-yielding deposits at the central

bank.

So the profit of the banking system has decreased.

Therefore, paying back too high amount will bankrupt the banking system. Nobody

wants that, with all the short-term financial instability it would introduce

into the system.

However, one has to remember that even though the net

interest income of banks has decreased, the net interest income (or cost) of households increases (decreases) by the same amount. This, of course, is the purpose of

this whole thing. Lower interest costs of households will boost their

purchasing power, net of interest costs, which will, if they spend it, increase the cash flows

between households and manufacturers of goods and services, hopefully boosting

investment and get employment going again. That, of course, applies only if the

firms are willing to get into investment projects and don’t use the cash flows

from households, in the form of sales, to decrease their own outstanding debts,

which of course would be a serious sign of a Koo-like balance sheet recession.

What about inflation

and the money supply?

The money supply does not increase by the SPV-channelled

debt jubilee itself because the deposits of households are unchanged and banks’

deposits at the central bank do not constitute as part of the money supply.

However, of course, the banks will try to lend out the money

immediately! That would expand the money supply. After all, money is only

created in the modern bank-credit economy through the lending activity of the

banking system (given that the central bank doesn’t print the cash). And since

the banks are always eager to lend out money – that’s how they profit,

especially in Iceland where majority of mortgages are indexed to the CPI – they will always try

to, and simultaneously create spendable deposits in the meanwhile. It is the central bank, as a head of monetary policy, which is responsible

for keeping money-and-loan creation of the banking system chained to economic reality.

The best ideas I’ve seen so far, regarding how to quantify the net amount the

Central bank should allow banks to create of loans and money, is Leigh Harkness’ proposal of

connecting bank lending to the current account & foreign reserves. See

Buoyant Economies for further

papers and opinions.

Finally, note that inflation may gain ground, temporally,

even though money supply does not spike along with newly created bank loans and bank customers’ deposits straight after the jubilee. The reason is that households

have more purchasing power. Therefore, demand-pull inflation may temporarily

set in.

Holy hell, is this an

infinite gold mine?

Evidently, this sounds like an infinite gold mine: since

this can be done without bankrupting anybody,

but merely redistribute future spendable income between banks and

households, why not just use this trick again

and again? But this isn’t an infinite gold mine; this is an economic act of

emergency like debt jubilees for the last millennia have always been.

Why not do this again and again? Because of the moral

hazard. If everybody knows that debt jubilee will be carried out whenever the

system is bankrupting itself with too much debt, there will be an

uncontrollable willingness to borrow as much as one can, as quickly as one can.

The banks would play along because their managers, especially if they get paid

according to short term profits in the form of cash bonuses and such, would be able

to get the net interest income, and their bonuses, on the way up and then flee

the ship as the jubilee would be coming. Short-termism is a serious and

continuous problem in the economy – ask any voter.

A systematic and repeated debt jubilee that everybody would

anticipate would have serious consequences on the macro economy because the

consequential and periodic debt explosions it would introduce into the system

would seriously unhinge the stability of the whole capitalist economy. It is

not only the repayment of debt that introduces serious instability into the

system, if there are no incomes to meet that need of debt repayments, but the

expansion of debt, if too rapid, introduces problems and instability as well. That problem, i.e. too much debt expansion, is of course the root of our economic problems of today.

Said all this, the need for a debt jubilee, especially in

debt stricken Iceland, is serious. The construction of the Icelandic economy is

such that the dynamic long-term development of it is unmistakably towards more

financial instability. The debt jubilee here described is part of a much-needed

overhaul of the economic system in Iceland and meant to provide breathing space

for households to carry out the rest of the reorganisation that is needed.

On

the top of the list of prioritised overhauls are the Icelandic pension system

and the system of price indexation of debt, both responsible for outrageously high

interest rates and too much ease of access to credit.