Ever since the "what's the difference between Iceland and Ireland?" joke, the comparison between the two economies has been frequent. I'm going to jump on the bandwagon and at the same time offer a rather pessimistic long-term view on Iceland, at least in comparison to Ireland.

First, the facts. GDP growth in Iceland has picked up and Iceland Statistics famously

reported growth of 3.7% over the first three quarters of 2011 compared to same period the year before. The

Central Bank of Iceland (not that I expect that institution to be right all the time) expects economic growth to be 3.0% in 2011 and 2.5% in 2012. Iceland is back on track!

Or so it seems at least. I'll get to it later why the optimistic view of the future is a misconception (I touch on it as well in this post:

Money and Debt in Iceland and the New Prosperity) but first, let me show you the track record of Iceland's economy compared to Ireland (and Spain and Greece).

Volume of GDP indices, seasonally adjusted and rebased to top=100. OECD figures. Economic growth in Iceland has always been volatile. Celebrating victory in "the race against the Irish" is therefore quite ill-timed and not only because of that reason.

The romantic view on Iceland

There is one misunderstanding apparent when Iceland and Ireland are compared. People seem to sometimes think that Icelandic people said "Oh, hell no! We're not going to save your arses, you just have to go bankrupt and that's the end of it" to the banks. Some people make a gesture to Icesave referendum to justify that point of view. Furthermore, the "splendid" 110% debt write-off that was passed by the parliament is considered to a fantastic success and shows on top of that the will of the people to simply get the banks to understand that debts that cannot or should not be repaid, won't be repaid.

Sorry, there is a bit of romanticism in this story.

First, the Icelandic government tried absolutely everything it could possibly do in 2008 to save the banks. It was Iceland's "fool's luck" to have allowed the banks to grow up to 1,000% of GDP that made the government rescue impossible. There was no other choice than to let the banks go bankrupt, even though it has been painted in the foreign media as "Iceland chose to let the banks go bankrupt instead of shoring up their broken pieces."

Second, the Icesave agreement was forcibly passed through the parliament by the government. It was the president that stopped the bill to become a law after the world of bloggers had been on fire for months while the public anger against the government ascended day by day. More importantly, the Icesave dispute had nothing to do with Icelandic "banksters" as they were called by that time. It was and is an international quarrel regarding how to interpret the EU/EEA treaty concerning deposit insurance schemes and passport-banking within the EU. Icesave wasn't and isn't a question of bailing out the banks.

Third, the 110% debt write-off that was introduced by the government hasn't been that successful and certainly not very influencing in the overall scheme of things.

The 110% debt write-off was simply a measure that was offered to over-indebted households. It was very simple on the surface: if your mortgage was higher than 110% of the estimated market value of the property, you could have the debt written off down to the 110% mark.

The total debt that was written off based on this jubilee was

43.6 billion krona. On top of that came 6.2 billion due to "special measures". In comparison, the debt that was written off due to

illegal foreign-exchange-linked loans was 146.5 billion krona. In September 2008 (the last point in time where it is known how high the face value of household debt was) the debt of households was 1,890 billion krona (128% of GDP). The government induced debt write-off has been roughly 2.5% of the total debt of households. Is that meant to be a huge turning point? Give me a break! The indexed debt of households has in the meanwhile risen by a rough estimation of 200 billion ISK due to rise in consumer prices since 2008. This is not a typo.

Longer term view

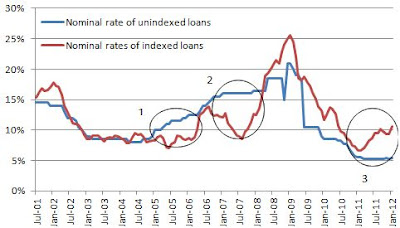

The debt dynamics in the Icelandic economy are scary! The mortgage and financial system is built to collapse, it is an unmissable feature of the organisation of the system. Real rates on debt that is founded on money traded in the secondary market (after the money has been created by the banking system) have a legal floor of 3.5% due to the legal structure of the pension system and its sheer size within the economy. The 3.5% floor has only been broken recently due to the capital controls locking in the money in the economy. When they are lifted, whenever that will be, the bubble on the bond market will implode and the yield rocket up to the floor once more when pension funds and other investors get out of the economy in search for higher yield, even if that will cost bearing higher risk in the form of investing in international stock markets.

In the meanwhile, most mortgages are indexed to the Consumer Price Index. The key to the long-term instability in the organisation is that the nominal interest rates are not what is indexed to changes in the CPI but the actual principal of the loan is indexed to the value of the CPI itself. This effectively means that every time there is a rise in the CPI, the borrower "gets" an automatic loan from the lending institution in the form of the fact that he doesn't have to pay the cost of the indexation at that point in time. One of the rationale behind why this mad system is meant to work is that borrowers are supposed to be forward looking and anticipate today that they have to pay their increased debts due to higher nominal value of their indexed mortgage in 20 years time. Give me another break!

No, Ireland and Iceland are not the same. Iceland may have the upper hand now because the GDP growth figures of 2011 and perhaps 2012 are and will be more favourable in the case of Iceland. But Ireland does not have to fight as mad mortgage and financial system as the Icelandic one and that is what will chain Iceland down in the longer run.

Plus, Ireland has Guinness! And leprechauns!

Do those graphs seriously give the impression that the Icelandic economy is healthier than the Irish one? Data from European Mortgage Federation. Author's calculations on the interest rates in case of Iceland's economy.