In early December, Statistics Iceland issued the GDP figures

for 3Q 2011. The figures were, taking into the account how massive the global

economic instability and lack of growth still are and the fact that Iceland’s

banking system went magnificently bankrupt, rather surprising: 3.7% GDP growth

over the first three quarters of 2011 compared to the same period the year

before! Iceland was back on track, leaving Europe in the dustbin!!

The Central bank seized the opportunity and claimed

economic recovery was already there. Therefore, people should not really be

surprised about the rate hike in early November (rates stand at 4.75%), especially since the labour

unions managed to squeeze out a considerable nominal wage rate increase and

that would, “of course”, lead directly to higher inflation in the close future.

The government did the same, claiming the honour for the recovery and politely

asked those who were always complaining about high unemployment and debts

while pointing out record number of people leaving Iceland, most notably to

Norway, to keep quiet. The recovery was here, no need to continue whining!

Many were still rather sceptical, simply because the debt

shock since 2008 was still around and due to mad indexation of mortgages the

debt wasn’t going anywhere despite write offs of (illegal!) foreign currency

denominated loans and other weak debt reduction schemes. But the “World In Balance Sheet Recession” paper by Richard Koo, author of the outstanding “Holy

Grail of Macroeconomics”, just opened my eyes. Iceland was in a “Lehman Brother

shock” and the balance sheet recession (too much debt) wasn’t going anywhere

even though the figures of Statistics Iceland claimed otherwise.

Exhibit 16 in Koo’s paper fits the Icelandic economy like a

glove! Substitute “Lehman” with “Icelandic banks” and the explanation is

perfect.

The argument is as follows. The over indebtedness of

Icelandic firms and households in 2008 was too great and balance sheet

recession – a recession where firms and households in the economy cannot

maintain normal economic activity due to high debts – was already on its way.

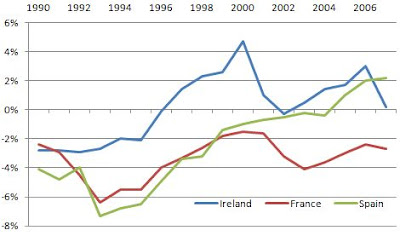

That should not be surprising: the Icelandic non-financial sector was the most

indebted one in whole of Europe and Icelandic households were close to the top

of the list by indebtedness. Furthermore, the banks themselves were

deleveraging (“deleveraging while delivering” was the punch line of

Kaupthing just before it filed for bankruptcy) so macro deleveraging of the

whole economy was the upcoming game in late 2007 and early 2008. That corresponds to the light-blue broken

line on the diagram.

But the banks went bankrupt, not because of policy mistake

like Koo says was the case of Lehman in US, but simply because there was

nothing else in the cards. In fact, the government did its utmost to save the

banks but, fortunately (if we look at Ireland) we simply couldn't. Sometimes it’s

good to be impotent.

When the Icelandic banks went down under just a few weeks

after Lehman the Icelandic economy was shocked and went down the solid dark blue

line instead down the light blue broken path. The economy crashed! Spectacularly in fact, economic growth for 2008-2010 was -9.3%.

Today, the

growth of 3.7% is not because the “recovery is here” but because the economy

has cleared the actual bank-bankruptcy shock out of the system and is edging

closer to the balance sheet recession path (light blue line). This recovery is

in other words the upward sling of the solid dark blue line.

So the growth is there, no reason to doubt that. But the

problem is that the economy isn’t recovering like the Central Bank of Iceland

and the government claim. The balance sheet recession is still there. And that

can best be seen in the fact that investment is still a puny part of the

economic activity: nobody wants to borrow for other things than possibly

speculate a bit with housing while capital controls are still in place. While nobody is borrowing, nobody is investing in real capital and nobody is

hiring or creating productive real capital. That can only mean one thing: a long term weak economy that is fighting over indebtedness of households and firms.

Investment is still at historically low levels despite "economic recovery". That implies balance sheet recession where firms and households are trying to minimise debt, i.e. deleveraging, rather than maximising profits.

First rule of balance sheet recessions: people try to

deleverage their balance sheet and they certainly do not do that by borrowing

and investing in real capital. Second rule of balance sheet recessions: we do

not talk of them, because they do not confirm our little trouble-free

economics.