The following interview was with Jorge Rodriques, journalist of Exame in Portugal. This is the English version - plus some additions on the Minsky moment - but the Portuguese version is due later in the week.

The original source is

here. Jorge added some very informative and good details on the general economy and the ongoing criminal cases as well so please refer to his site for further info.

-----------

Q: Analysts and economists all over Europe praised a lot the “Iceland miracle” of last decades. Until the Great Recession came. Iceland was in the 2000s the extreme example of the financialisation of the economy and the society, worse than the US, Ireland and Spain?

A: It depends on how you look at it. Financialisation in the sense of just trading financial instruments in between the more or less same market participants was certainly more prominent in the case of say the US than in the case of Iceland. However, at the height of the bubble, the Icelandic financial industry share of GDP topped at 9.4% in 2005 and 2006. That’s a higher ratio than even in the US. That fact becomes even more shocking when one realises that in 1997 the share of the financial industry of the GDP was 4.6%. So in less than 10 years, the finance industry more than doubled its share of the GDP and reached higher levels than even in the case of US. So yes, from that point of view the financialisation of the Icelandic economy was probably even more extreme than in the case of many other countries.

Q: Another aspect of the “miracle” that is intriguing. What was behind the so-called “entrepreneurial neo-Vikings” and the entrepreneurial economy of last decades?

A: Credit! Credit created out of thin air by the banking system, simple as that. We of course fooled ourselves into thinking that it had something to do with the Icelandic Viking spirit, the energy of the young (and inexperienced) leaders of the leading companies, the free-market movement of the 1990s, and even the rugged and “therefore” hardening Icelandic natural environment. But there was in essence no secret formula about the temporary prominent status of the Icelandic entrepreneurial Viking. He had credit, created by nothing by either a foreign bank he managed to fool into his scheme or the newly privatised Icelandic banks that sometimes he himself or his friends had a controlling share in. And, that was that.

Q: You are writing a book about Bad Economics and the impact in the Iceland economy. Iceland was the typical example of an economy that was ruled by bad economics?

A: Yes, and it still is! But I must be absolutely clear on the point of the “bad economists”. I do not believe that any of the leading economists were or are “bad” in any sense of that word. I believe all of them were acting in absolutely good faith, trying to improve the economy and society. But intentions are not enough if you don’t have the tools.

Q: Which theories and schools of Economic thought must be blamed?

A: The tool that failed spectacularly was the neoclassical school of economics. Only a small handful of economists did not rely on this, unfortunately, globally ruling way of doing economics. They were the only ones that were not blinded by neoclassical theories when the bubble began to expand beyond point of no-return. But when they tried to warn the community about what was happening the neoclassical economists ridiculed them, not because they were “bad” but because they were blinded by their faith in neoclassical economics.

HIGHLIGHTS

«I must say that the Icelandic case was a quintessential example of the Minskyian theory»

Q: Can we say there were signals of a “Minsky moment” – from the name of the North-American economist Hyman Minsky that from early 1980s talked about a systemic financial process risking a new big Recession like the Great Depression of the 1930s – coming for Iceland in the end of the 2000s?

A: It’s always tough to pinpoint accurately when the exact Minsky moment arrives. But Minsky “Financial Instability Hypothesis” was certainly proved to be the most accurate economic thesis in existence when the Icelandic boom-and-bust cycle took place. I must say that the Icelandic case was a quintessential example of the Minskyian theory.

Q: How?

A: [The way up was very much like Minsky predicted. The atmosphere was euphoric, everybody wanted to make a quick buck! After a very short contraction period in 2002 the economy bounced back. Confidence grew again and when the banks were privatised in 2003 the economy boomed, driven by credit creation by the banks and people's confidence. When the credit sparked asset price inflation, all the Johns and Joneses jumped on the bandwagon and used credit to buy existing assets. An asset boom developed hand in hand with the foreign direct investment flow that was due to construction of aluminium smelter and a hydro dam in the east part of the country. Everybody forgot the lessons of 2000 and 2001 when the credit boom that took place then fuelled a stock speculation boom in Decode Genetics. That exploded fantastically! A short sober moment arrived in 2006 but the self-delusion was too strong and people reinforced their beliefs in the Icelandic miracle after the 2006 doubts had been wiped out. Foreign currency loans took over the indexed ISK loans as the main credit device fuelling the boom. Then finally, the asset price inflation slowed down and the Ponzi-positions began to lose out. Liquidity squeeze shortly followed.]

When it comes to the downturn especially we can, e.g. notice that the stock index topped above 9000 points during the summer of 2007 before finally collapsing below 500 in 2008. The liquidity shortage was also very much as Minsky predicted and the margin calls became more and more prominent. In 2008 the Central Bank stepped in and tried to supply liquidity into the market, but it didn’t suffice to stop the avalanche.

HIGHLIGHTS

« Yes, there is growth again in Iceland, but there is unfortunately not much behind it.»

Q: As you know today Iceland is a near-myth again because the island is returning to “broad based growth,” said the IMF mission chief to the Icelandic program. Are we assisting to an adjustment “miracle” praised by the IMF?

A: Yes, there is growth, but there is unfortunately not much behind it. The reason I say this is that when we dig deeper into the national account figures they kind of lose their surface charm. Gross investment is, e.g. still meagre 12-15% of GDP, which is hardly enough to maintain the base of productive capital in the economy. The present 4.7% unemployment rate [from a peak of 9.3 percent two years ago] does not include those who have given up on looking for a job and have either moved out of the country [in 2011, Census reported that 8% of population migrated mainly to Norway] or decided to go back to school, sometimes just to do something. As a signal of the stagnant labour market, the average number of worked hour per individual in the working force has been stagnant since 2009. And, interest rates are still too high, which is an especially poisonous goblet when the indexation of mortgages is mixed with it. Also, the banks and the State sponsored Housing Financing Fund (HHF) are not very eager to liquefy their stock of empty houses and flats, due to their fright of crashing the housing market by doing so. As a clear sign of that, the HFF repossessed 501 flats and houses during the first six months of 2012, but sold only 58 flats at the same time. Finally, the number of individuals with severely delayed repayments of their debts is still rising.

Q: But there’s no reason for optimism, more than in Ireland or Portugal, the so-called “good pupils” of the troika medicines?

A: There is growth, but it is froth. I do not see much reason for any spectacular optimism about the long-term future of the Icelandic economy. The structural deficits that got us into the hole we’re still trying to dig us out of are still there and that is what makes the long-term difference. We have to fix those if we are ever to have a stable economy.

Q: What you mean by “structural” problems?

A: The structural problems that I have in mind are specifically the indexation of mortgages and the pension system, which not only has a huge funding hole but influences the financial market strongly due to its size. The effects of those problems push up the rate of interest and introduce structural financial instability into the economy, instability that does not have to be there and is not caused by anything else. Fixing those structural problems would strengthen the financial stability in Iceland to a significant and notable extent. But work is going too slowly in that field, those problems are still around.

Q: In Iceland there was not TBTF (too big to fail) banks and TBTJ (too big to jail) banksters or government officials?

A: I cannot comment much on the TBTJ, the Special Prosecutor is investigating the cases that end up on his table and we must be patient and allow him to do his job. He has landed some victories though, such as the conviction of the ex-finance ministry undersecretary Baldur Gudlaugsson [This was the first time an insider dealing case has ever been tried at the Supreme Court of Iceland. Baldur was found guilty by the Reykjavík District Court on 7th of April 2011 and sentenced to two years behind bars. An appeal against that decision fails in Supreme Court in February 2012] and the “Exista case” [Exista is a financial services firm founded in 2001 by a consortium of Icelandic savings banks as a vehicle to hold shares in Icelandic Kaupthing Bank. A controlling shareholding in the firm was sold to a holding of the brothers Ágúst and Lýdur Gudmundsson in 2002. An IPO went on 2006 in Iceland Stock Exchange for €2.6 billion, the biggest IPO in the country's history. By October 2008, Kaupthing Bank was forced into government receivership, it was nationalized de facto. In July 2009 Wikileaks exposed a confidential 210 page document listing Kaupthing's exposure to loans. The bank had loaned billions of euros to its major shareholders, including a total of €1.43 billion to Exista and its subsidiaries which own 23% of the bank. In January 2010 law enforcement agents from Britain and Iceland searched the premises of Exista in a probe related to the trading of shares in other companies].

HIGHLIGHTS

«The whole Icelandic financial system went down the drain, but the payment system was maintained thanks to tremendous efforts by the staff of the Central Bank.»

Q: And regarding the TBTF banks?

A: The question of TBTF banks is very interesting in the case of Iceland, however, and I think it deserves more attention than it has gotten. The definition of a TBTF bank is that it is too systematically important to be allowed to fail since otherwise the financial system would collapse, general commerce in the wake of that and consequently the whole economy. But that didn’t happen. Yes, the whole financial system went down the drain, but the payment system was maintained thanks to tremendous efforts by the staff of the Central Bank. And, since the payment system was kept intact, commerce kept on and the economy did not crumble entirely. We could still buy our pints of milk and bakeries still baked their breads. And, they kept on accepting card payments.

Q: How it happened the “miracle”?

A: The reason for why the payment system did not collapse was that it is centralised entirely through the Central Bank itself. That means that the Central Bank can allow a bank, no matter how big it is, to go under since it isn’t a clearing bank for any of the general every day commerce that everybody expects to be able to do. This is not the case in many countries, such as the UK. This structure of the payment system – the Central Bank is the only clearing bank of the whole payment system of everyday commerce – was the essence of why the payment system did not collapse even though 90% of the banking system, by assets, went bankrupt in a time span of only a week. This is the fundamental lesson for other nations: channel the whole payment system through the Central Bank and no bank is too big to fail when it comes to every day commerce.

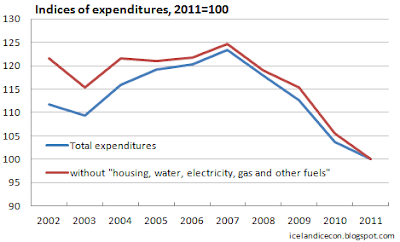

Q: What kind of fiscal austerity measures were adopted that permitted the fiscal deficit cut from near 14pc of GDP at the end of 2008 to 5.7pc for 2011?

A: Well, the 13.8% fiscal deficit in the last quarter of 2008 was a one-off cost: it includes the new equity injection into the Central Bank (yes, the equity of the Central Bank of Iceland was wiped out in October 2008 – the Central Bank went bankrupt!). So let’s make sure not to think that the politicians have managed to cut the deficit from 14% of GDP to 5.7% by austerity alone. The austerity measures in Iceland were in fact not as severe as in say Spain, Portugal or Greece. The welfare system was more or less maintained, beside extensive cuts in health care to such a level that they have had to use sticker tape to temporally fix some of the cancer treating equipment in the main hospital in Reykjavik. Health service outside the capital has also been guillotined quite severely. Taxes were raised as well. A special net-wealth tax was adopted, VAT was raised, now commonly 25.5% though lower steps exist as well, and the tax rate on wages was increased. Same goes for taxes on capital gains, now 20% instead of 10% before. Personal tax return for individuals was increase as well however, having the effect that most of the increased tax burden was carried by the richer part of the population.

HIGHLIGHTS

«But the currency crash – the depreciation of the krona – also caused inflation and that led to higher principals of our debts, debts that many people will never be able to repay.»

Q: The depreciation of the krona was the main tool for the adjustment?

A: Yes, the crash of the krona was the main tool of the external adjustment. It however, lead to even further internal imbalance since the crash of the exchange rate lead to increased inflation and that increased the principal of the inflation-indexed mortgages and many other debt instruments. This imbalance is still being dealt with and it will take a while.

Q: Can you explain better that downside risk?

A: Yes, this needs some explanation. The mortgage system in Iceland is such that the monetary value of the principal increases hand in hand with the inflation. So if one borrows say 100,000 kronas mortgage and the inflation rate is 5% over next year, the debt increases up to 105,000 kronas. Then, the repayments are made, but the repayment of the increase of the principal is spread out over the whole remaining loan period. The currency crash therefore had the effects of increasing the competitiveness of Icelandic goods, thereby allowing us to rebuild the economy on the basis of exports and tourism. But the currency crash also caused inflation and that led to higher principals of our debts, debts that many people will never be able to repay.

Q: It would be better if Iceland defaulted in its sovereign debt and implemented a full restructuring debt process?

A: No, it would not. It would, however, be a good idea to carry out some sort of debt jubilee for the private individuals and enterprises in the economy. And, that can be done, the only thing that is needed is the political will to do so. But if the State defaults on its debts we would probably have even more serious problems on our hands. Yes, national States have defaulted on their debts before and later arisen out of their economic ashes like the phoenix, but it is a high risk and absolute last resort measure. But in some cases, for example some present economies in the Eurozone, such last resort measures are exactly the ones that are needed. But the finances of the Icelandic State are not, yet that serious. So sovereign default is probably not a good idea for Iceland, at least not yet.

Q: Would you refer specific “growth policies” pursued by the government?

A: Not in particularly anything else than those that aimed at lessening the hit of the financial crisis immediately after it happened. The fight against IMF-demanded austerity should be highlighted though. There is a plan to get government funded investment going during the years of 2013-2015. Included in that plan is, e.g. general road network maintenance and increased subsidies to high-tech and technology development funds, etc. The financing of this plan is meant to come from road tolls and fees on fish catches, born by the fishing industry. This may not become realised, however, as there are general elections next spring.

HIGHLIGHTS

«The question about who are the real owners of the Icelandic banks is very good: we do not know! People have speculated a lot about this. Foreign shark hedge funds are one theory, the old domestic “entrepreneurial Vikings” is another and on the theories go.»

Q: If the sovereign debt skyrocketed after 2008 can we say it was for a good reason, for the relief of the households and corporations debt? Or the so-called debt forgiveness is another myth?

A: The severe increment of government debt after the 2008 was first and foremost due to the rescue of the Central Bank of Iceland which lost the equivalent of about 20% of GDP when it lent money to the banks against lousy collateral. When the banks went bankrupt, so did the Central Bank. The cost of injecting new equity into ended on the shoulders of the taxpayer. That cost was around 400 billion ISK according to The Icelandic National Audit Office. The so-called debt forgiveness of household and corporate debt did not cause any severe, if any when everything is taken into account, cost for the State. The banks bore all the “cost” but it effectively did not impair their equity at all. The reason for that is that when the new banks were established on the foundations of the fallen ones, the assets were booked in the new banks at about 40% discount. A 100,000 krona loan became a 60,000 krona loan on the books of the new banks. This magic did not, however, continue to the borrower himself, he still owed the bank 100,000 krona. It was this discount that was used to cancel the majority of the debt that was actually cancelled. In February, the households had been forgiven 196 billion ISK (12% of GDP) but that was pretty much all outweighed by the indexation of mortgages, so the net cancellation was rather limited. Firms got a lot more cancelled, around 550 billion ISK. And, of course, not everybody got the equal amount cancelled. Eight firms got cancelled the total of 205 billion ISK. In fact, most of the firms that got debt cancelled were asset holding firms, many of them totally empty of assets after the collapse. So their debts would have had to be cancelled anyway, simply due to the liquidity process behind their bankrupt itself.

Q: After the banking restructuring, who benefited most from it? Who are the real owners of the Icelandic banks today?

A: I think this must have been the most indebted firms that benefited the most, simply because they got the most of the debt cancellation. And, the question about who are the real owners of the Icelandic banks is very good: we do not know! People have speculated a lot about this. Foreign shark hedge funds are one theory, the old domestic “entrepreneurial Vikings” is another and on the theories go. But quite frankly, we simply do not know.

DIFFERENCES WITH THE TROIKA EUROZONE BAIL-OUTS

«If the austerity had been as unforgiving as the one that is in mainland Europe the Icelandic economy would not have been given the breathing space to recover from the shock.»

Q: What are in your view the main differences of the Icelandic strategy relative to the adjustment programs adopted by the so-called troika EU/ECB/IMF in the Eurozone?

A: The Icelandic austerity was not as severe and the increment in taxation was more directed towards the richer end of the populace. I believe that was the right thing to do, if the austerity had been as unforgiving as the one that is in mainland Europe the economy would not have been given the breathing space to recover from the shock. Socially, it was probably healthier as well to let the rich carry most of the austerity burden, otherwise we could have had general riots and another “pots and pans” revolution. Another important difference was that we were capable of allowing the currency to devalue and that helped although the homemade structural deficits of indexing debt to the level of consumer price probably just switched out the problem of external imbalance with an internal one. Being able to allow the banks to go under while maintaining the payment system was a huge advantage as well.

Q: That is one of the “lessons” that you think universal…

A: Yes. The Troika could learn tremendously of the Icelandic experience in that case, it would save them the problem of having to save the whole banking system repeatedly. Banks should, as any other firms, be allowed to go bust! Finally, there were some debt cancellations although they were more or less just to wind down part of the indexation problem when it comes to the households in particular. But debt cancellations are doable; one just has to find the political courage to carry them out.

Q: How did Iceland deal with the IMF?

A: IMF did propose more austerity and did for example propose more severe cuts in the welfare system. That was refrained and probably for the good. The adjustment process, especially the cut in fiscal deficit, was slowed down in comparison to the IMF proposal.

Q: Will Iceland abandon the krona and adopt the Euro, or it will choose a different strategy searching a non-European currency?

A: I cannot say. The official stance is to gain entry into the EU and adopt the Euro. But to fulfil the Maastricht guidelines on Euro could take us as long as a decade and the EU will have transformed significantly in as short time as half that. So to adopt the Euro will probably take us a while, given that there will be political will after the 2013 elections to finish the EU entry process.